Why Clothes Smell Damp Even When Clean

The Hidden Role of Moisture, Bacteria & London’s Climate

When Clean Clothes Still Smell Wrong

Why clothes smell damp even when clean is one of the most common — and most misunderstood — garment‑care complaints in London homes. Clothes come out of the washing machine or dry cleaner looking spotless, feeling soft, and appearing perfectly fresh. And yet, a few hours later, that faint musty, sour, or damp smell creeps back in.

This problem isn’t rare. In fact, it’s almost normal in London. Period homes, modern flats, and apartments across NW London struggle with high humidity, limited airflow, and indoor drying. Washing more often doesn’t solve it — it usually makes it worse.

Here’s the truth most people never hear: this issue has very little to do with hygiene, detergent quality, or how often you wash. The real problem lies within the fibres — where moisture and bacteria persist long after clothes appear clean.

This guide breaks down why clothes smell damp even when clean, how London’s climate amplifies the issue, and what actually fixes it — for good.

Still dealing with damp-smelling clothes after washing?

Repeated home washing often traps moisture deep inside fabric fibres. Our professional laundry service in Hampstead removes odour at the source—not just masks it.

👉 Book a laundry collection in Hampstead

Why Damp Smells Persist in London Homes After Washing

In London homes, damp odours often return after washing because moisture remains trapped deep within fabric fibres. High indoor humidity, limited airflow, and indoor drying slow down internal evaporation, allowing bacteria to survive even when clothes appear dry on the surface.

This effect is amplified by frequent washing at low temperatures and detergent residue buildup, which creates an ideal environment for odour-causing microorganisms. As a result, the smell is not removed; it is merely reactivated.

Why Clothes Smell Damp Even When Clean in London Homes

This is the core issue almost everyone misses.

This is the core issue almost everyone misses.

A garment can appear clean yet remain unhygienic. When clothes are washed, water penetrates deep into the fibre structure. During drying, the outer surface dries first, while the internal fibres, especially in thicker fabrics, retain moisture.

In London homes, clothes are commonly dried:

-

Indoors on airers — Airers dry clothes slowly and unevenly. Moisture escapes from the surface, but without strong airflow, humidity builds around the garment, preventing internal fibres from thoroughly drying.

-

Near radiators — Radiator heat can dry the outside too quickly, trapping moisture inside thicker areas such as seams, cuffs, linings, and waistbands. Clothes feel dry on the outside but remain damp on the inside.

-

In bathrooms or kitchens—these are the most humid rooms in the home. Steam from showers and cooking increases moisture in the air, slowing evaporation and encouraging bacterial growth.

-

In poorly ventilated rooms without fresh air circulation, moisture has nowhere to go. Damp air recirculates around the garment, extending drying times and increasing the risk of odour.

Even when clothes feel dry to the touch, microscopic moisture often remains trapped inside. Once garments are worn or stored, body heat reactivates bacteria, and the smell returns.

This is why clothes smell damp even when clean — particularly in dense, humid urban environments like London.

Clean vs Hygienic: Why “Clean” Clothes Can Still Smell

One of the biggest myths in garment care is assuming that clean and hygienic mean the same thing.

One of the biggest myths in garment care is assuming that clean and hygienic mean the same thing.

They don’t — and the difference is critical.

-

Clean means free from visible dirt, stains, and surface grime. Clothes may look bright, smell neutral at first, and feel soft to the touch.

-

Hygienic means the fabric is free from trapped moisture, bacteria, mould spores, and organic residue deep inside the fibres.

Domestic washing machines are engineered primarily for appearance, convenience, and energy efficiency — not deep hygienic control. Standard wash cycles focus on loosening surface soil and rinsing it away, but they rarely address what happens inside dense fabrics, seams, linings, padding, and layered textiles.

In many washes, bacteria are not fully destroyed; they are merely disrupted. When drying is incomplete, these microorganisms remain alive but dormant. As soon as moisture, warmth, or body heat is reintroduced, bacteria reactivate and begin producing odour again.

This is why clothes can smell perfectly fine straight out of the wash, yet develop a damp or sour smell shortly after wearing or storage. The garment was clean — but it was never truly hygienic.

How Trapped Moisture Causes Clothes to Smell After Washing

Fabric isn’t flat. It’s a three‑dimensional network of twisted fibres, layered yarns, and microscopic air pockets — more like a sponge than a sheet of paper.

When a garment goes into the wash, water doesn’t just wet the surface. It is actively pulled deep into the fibre structure through capillary action, travelling along yarns, into seams, padding, cuffs, collars, and inner linings.

During washing:

-

Water penetrates fibre cores and internal yarn layers, not just the outer surface

-

Detergents dissolve oils, sweat, and organic residue that bacteria feed on

-

Rinsing removes most contaminants, but heavier oils and residues often remain bonded to fibres

The critical failure happens during drying.

As drying begins, heat and airflow remove moisture from the outside first. Fabrics feel dry because surface fibres lose water quickly. However, moisture trapped deeper inside the structure escapes far more slowly — especially where fabrics are thick, folded, stitched, or padded.

This delayed internal drying is most common in:

-

Winter coats and padded jackets (multiple layers, insulation, linings)

-

Towels and bathrobes (dense cotton loops that hold water internally)

-

Knitwear and wool garments (yarn structure traps moisture between fibres)

-

Bedding and duvets (large volumes of fabric with poor internal airflow)

While the garment may feel “dry” to the touch, pockets of moisture remain sealed inside. These damp zones are warm, dark, and rich in residual oils — the exact conditions bacteria need to survive and multiply.

This is why odour often appears after wearing or storage, not immediately after washing. Body heat reactivates bacteria in those damp pockets, triggering the release of odour‑causing compounds.

That trapped internal moisture is what turns a clean‑looking garment into a perfect breeding ground for bacteria.

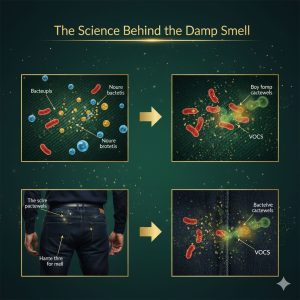

The Science Behind the Damp Smell

The damp smell isn’t caused by water itself.

The damp smell isn’t caused by water itself.

It’s caused by bacteria — and more specifically, by what bacteria produce when they survive inside fabric.

Bacteria don’t smell on their own. The odour appears when they metabolise leftover organic material trapped in fibres, such as body oils, sweat proteins, skin cells, and detergent residue. As they break these substances down, bacteria release volatile organic compounds (VOCs).

VOCs are microscopic gas‑like molecules. They evaporate easily, travel through the air, and are extremely noticeable to the human nose — even in tiny concentrations. Different VOCs create different odour profiles, which is why damp smells can register as musty, sour, cheesy, or stale depending on the fabric and bacteria present.

Crucially, washing often spreads moisture deeper into fibres without entirely removing the bacteria’s food source. So instead of eliminating the problem, repeated washing can reinforce it.

This is precisely why many Hampstead households turn to professional laundry services — designed to remove deep moisture and bacteria safely, rather than reactivating them through repeated home washing.

This is why:

-

Rewashing often doesn’t work — bacteria remain embedded inside fibres and reactivate after drying

-

Fabric softeners only mask odour temporarily — they coat fibres with fragrance while trapping moisture and residue underneath.

-

The smell returns soon after wearing — body heat warms the fabric, accelerating bacterial activity and VOC release

Unless bacteria and their fuel are removed at the fibre level, the odour cycle continues. The smell disappears briefly, then returns — because the source of the odour was never actually eliminated.

Why Different Fabrics Trap Moisture Differently

Not all fabrics behave the same way — because their fibre structure, surface chemistry, and moisture behaviour are entirely different.

Not all fabrics behave the same way — because their fibre structure, surface chemistry, and moisture behaviour are entirely different.

Cotton fibres are naturally hollow, like tiny drinking straws. When cotton gets wet, moisture is drawn deep into the fibre core through capillary action. This is excellent for absorbency (great for towels), but terrible for drying. Even when the surface feels dry, moisture can remain trapped within the fibre. This is why cotton towels, T‑shirts, and bed sheets are especially prone to damp smells — the bacteria live inside the fibre, not on the surface.

Wool behaves in a more complex way. Wool fibres are covered in microscopic scales and contain keratin, a protein structure that reacts to moisture and heat. Initially, wool repels water. But once moisture penetrates, it becomes trapped between fibre scales and within the yarn structure. Wool also retains warmth, which further encourages bacterial survival. This is why wool coats, knitwear, and scarves can smell musty even after careful cleaning — the moisture is held internally and released slowly over time.

Synthetic fabrics such as polyester and nylon don’t absorb water into the fibre itself, but they trap moisture between fibres and layers. These fabrics dry quickly on the surface, giving the illusion of dryness, while moisture remains sealed in seams, mesh panels, padding, and layered constructions. In blended garments (cotton‑poly, wool‑synthetic), different fibres dry at different speeds, creating uneven moisture zones where bacteria thrive.

Because each fabric traps and releases moisture differently, one‑size‑fits‑all washing and drying simply doesn’t work. Without fabric‑specific cleaning, controlled drying, and proper airflow, odour stays locked inside — no matter how clean the garment looks.

Real‑Life London Example: The Winter Coat Problem

A classic London scenario:

A winter coat is cleaned at the end of the season. It smells fine, feels dry, and even passes the quick sniff test when stored away. Months later, within minutes of wearing it, a damp, musty smell suddenly appears — often strongest around the lining, underarms, or collar.

A winter coat is cleaned at the end of the season. It smells fine, feels dry, and even passes the quick sniff test when stored away. Months later, within minutes of wearing it, a damp, musty smell suddenly appears — often strongest around the lining, underarms, or collar.

What actually happened is far more gradual than people realise.

During cleaning, moisture penetrated deep into the coat’s internal structure — not just the outer fabric, but the lining, interfacing, padding, and stitched seams. These inner layers dry far more slowly than the surface. Even extended air‑drying or a standard tumble‑dry cycle often fails to remove all internal moisture from a structured garment like a winter coat.

When the coat was put into storage, it wasn’t wet — but it wasn’t fully dry either. Microscopic moisture remained locked inside the lining and padding. In a typical London wardrobe with limited airflow, that moisture had nowhere to escape.

Bacteria didn’t grow aggressively during storage; instead, they entered a dormant state. Dormant bacteria don’t produce strong odours, which is why the coat seemed fine for months.

The moment the coat was worn, everything changed.

Body heat warmed the fabric, increasing internal humidity and activating the bacteria. As they reawakened, they began breaking down residual oils left in the lining from previous wear. This metabolic activity released volatile organic compounds into the air, which is why the smell appeared suddenly and intensified within minutes.

This is why airing the coat outside briefly may help, but rarely solves the issue permanently. The odour isn’t sitting on the surface; it’s being generated from within the garment itself.

This isn’t a cleaning failure. The coat was cleaned. It’s a moisture‑control failure — where internal layers were never fully dried or stabilised before long‑term storage.

Why Gym and Activewear Smell Worse Over Time

Gym clothes are another frequent — and often frustrating — complaint.

Modern activewear is engineered to wick sweat away from the skin, dry quickly, and feel lightweight. To achieve this, manufacturers use tightly woven synthetic microfibres designed to move moisture along the surface. The problem is that these same microfibres also trap sweat oils deep inside the fabric structure.

Sweat itself is mostly water, but it carries fatty acids, skin cells, proteins, and salts. When you exercise, these oily compounds are forced into the microfibre network under heat and pressure. Domestic washing is very effective at removing surface sweat, but it struggles to dissolve and flush out oil‑based residues that have bonded to synthetic fibres.

Each wash cycle adds water and heat without fully removing these oils. Bacteria survive inside the fibres, feeding on the trapped residue. Because synthetic fabrics dry quickly on the surface, they often feel clean and dry — even while bacteria remain active inside.

Over time, this creates a compounding effect:

-

Bacteria populations increase with each wear

-

Odour‑causing compounds bind permanently to fibres

-

Smell appears faster and more intensely during exercise

This is why gym clothes can smell fine straight out of the wash, yet develop a strong odour within minutes of sweating. At this stage, standard home washing no longer breaks the cycle.

Without specialised treatment that targets oil residues and controls drying at the fibre level, odour in activewear gradually becomes permanent, which is why professionally treated gym clothing often feels noticeably fresher and lasts far longer.

Why Clothes Smell Damp Even When Clean During Winter

Winter makes everything worse in London — and not just because it feels colder.

During the winter months, the entire indoor environment changes in ways that actively work against proper fabric drying. Windows stay closed to retain heat, natural sunlight is limited, and heating systems warm the air without removing moisture. The result is a home that feels warm but remains surprisingly humid.

In these conditions, clothes often never reach full internal dryness. Surface fibres dry, but moisture trapped deep inside yarns, seams, linings, and padding escapes extremely slowly. Even tumble dryers can struggle unless extended cycles are used, because many machines shut off once surface dryness is detected — not when internal moisture is fully removed.

Winter also creates a perfect storm of compounding factors:

-

Drying times increase — cold outdoor air and indoor humidity slow evaporation

-

Indoor humidity rises — showers, cooking, and drying clothes indoors add moisture to already stagnant air

-

Air circulation drops — closed windows and sealed rooms trap damp air around garments

Because of this, bacteria are far more likely to survive winter wash cycles. They remain dormant while clothes cool, then reactivate during wear when body heat warms the fabric and raises internal humidity.

This is why clothes that seem fine in summer suddenly develop persistent damp smells in winter. The cleaning process hasn’t changed — the environment has. And in London winters, that environment strongly favours moisture retention and bacterial survival.

Common Home Laundry Mistakes That Make Damp Smell Worse

Many well‑intentioned laundry habits actually make damp smells worse — especially in London homes.

Overloading the washing machine

When a washing machine is overloaded, clothes cannot move freely. This reduces mechanical action, prevents detergent from circulating properly, and weakens rinsing. Oils and bacteria are loosened but not fully removed, then redistributed across the load. Heavy, compacted fabrics also retain far more water after spinning, meaning garments start drying already internally damp.

Using too much detergent

More detergent does not mean cleaner clothes. In hard‑water areas like London, excess detergent fails to rinse out, leaving a sticky residue on fibres. This residue traps moisture and feeds bacteria. Over time, detergent build‑up actually locks odour into fabric instead of removing it.

Stopping drying when clothes feel dry

Surface dryness is misleading. While the outside of a garment may feel dry, internal areas such as seams, waistbands, cuffs, collars, linings, and padding can remain damp for hours. Ending drying too early traps this moisture inside, allowing bacteria to survive and later reactivate.

Storing clothes while still warm

Warm fabric holds humidity. Folding or hanging clothes immediately after drying traps heat and moisture inside wardrobes and drawers. This creates a micro‑climate that allows bacteria to remain active, even if the garment smelled fine moments earlier.

Correcting these habits helps reduce future problems. However, once damp odour is embedded at the fibre level, habit changes alone are rarely enough to remove it completely.

Practical Home Steps That Reduce Odour Recurrence

These steps help control moisture — and when done correctly, they significantly reduce how often damp smells return.

Dry clothes fully, even if it takes longer

Dry clothes fully, even if it takes longer

True drying means internal dryness, not just surface dryness. Thicker areas such as seams, waistbands, cuffs, collars, linings, and padding hold moisture long after the outside feels dry. Extending drying time — whether air‑drying or tumble‑drying — allows this internal moisture to escape, reducing the environment bacteria need to survive.

Use less detergent, not more

Excess detergent leaves residue inside fibres, especially in London’s hard‑water conditions. This residue traps moisture and feeds bacteria. Using the correct amount allows garments to rinse cleanly, dry faster, and stay fresher for longer.

Let clothes cool and breathe before storage

Freshly dried clothes are warm and still releasing moisture vapour. Hanging or folding them immediately traps humidity inside the fabric and inside wardrobes. Allowing garments to cool in open air stabilises moisture levels and prevents odour from forming after storage.

Use dehumidifiers in drying areas

Indoor drying without moisture extraction simply moves water from fabric into the air — where it then re‑enters the garment. Dehumidifiers actively remove moisture from the environment, dramatically improving drying efficiency and reducing bacterial survival.

Improve wardrobe airflow

Wardrobes often become humidity pockets, especially in winter. Improving airflow — spacing garments, avoiding overcrowding, and allowing occasional ventilation — prevents moisture build‑up and stops dormant bacteria from reactivating.

These steps are highly effective at reducing recurrence and slowing odour development. However, they cannot remove bacteria, oils, and moisture that are already deeply embedded inside fibres. Once the odour has reached that stage, corrective treatment beyond normal home laundry is required to fully reset the garment.

Is Damp‑Smelling Clothing a Hygiene Concern?

Yes — and it’s more serious than most people realise.

Persistent damp odour is a strong indicator of ongoing bacterial activity and, in some cases, fungal growth within the fabric. These microorganisms thrive in moist, warm environments and can survive long periods inside textiles that are repeatedly washed but never fully dried internally.

For people with sensitive skin, this can lead to itching, redness, or flare‑ups of conditions such as eczema or dermatitis. For those with allergies or asthma, inhaling odour‑causing compounds and microscopic spores released from damp fabrics can trigger respiratory irritation, coughing, or discomfort — especially when garments are warmed by body heat.

The risk is higher with items that remain in close or prolonged contact with the body. Bedding, towels, underwear, gym wear, and sleepwear absorb large amounts of moisture and skin oils, creating ideal conditions for bacterial survival when hygiene is incomplete.

Damp‑smelling towels and bedding are particularly concerning because they are used repeatedly and often stored in bathrooms or bedrooms where humidity is already elevated. Over time, this creates a cycle where fabrics never fully reset hygienically, even though they are washed frequently.

In short, persistent damp odour isn’t just an inconvenience or a cosmetic issue. It’s a warning sign that a garment or household textile is no longer hygienically stable and may require deeper intervention to protect both fabric quality and personal comfort.

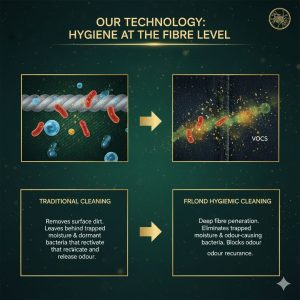

How Professional Garment Care Removes Odour at the Fibre Level

Professional garment care differs from domestic washing because it is designed to control moisture, chemistry, and time at the fibre level—not just to make clothes look clean.

Targeted pre‑treatment for oil residues

Targeted pre‑treatment for oil residues

Before complete cleaning begins, garments are assessed by fabric type, construction, and contamination. Oil‑based residues from skin, sweat, cosmetics, and environmental pollution are treated separately because standard washing does not dissolve them effectively. Removing these residues is critical, as they are the primary food source for odour‑causing bacteria.

Controlled washing environments

Professional systems use precise water temperatures, calibrated chemistry, and controlled agitation based on fabric behaviour. This prevents bacteria from merely being disturbed and redistributed — instead, it reduces their survival rate while protecting fibre integrity. Domestic machines prioritise energy efficiency; professional systems prioritise hygienic stability.

Extended, monitored drying cycles

Drying is where most home laundering fails. Professional drying does not stop when garments feel dry. Moisture sensors, airflow control, and extended cycles ensure that internal fibres, seams, linings, and padding are properly dried. This step alone dramatically reduces odour recurrence.

Post‑clean ventilation and stabilisation

After drying, garments are allowed to cool, ventilate, and stabilise before storage or packaging. This releases residual humidity and volatile compounds, preventing moisture from being trapped back into the fabric. It is a crucial but often overlooked step in long‑term odour prevention.

Together, these processes remove moisture, bacteria, and their fuel at the fibre level. That is why professionally treated garments do not just smell better temporarily — they remain odour‑stable over time, even in London’s challenging indoor climate.

Long‑Term Wardrobe Habits That Prevent Odour

Once odour is removed, prevention becomes simple — but only if these habits are understood and applied correctly.

Let garments breathe before storage.

After wearing or cleaning, fabrics hold residual heat and moisture vapour. Allowing garments to hang in the open air for a period allows internal moisture to escape. This stabilisation step prevents moisture from being trapped in fibres when clothing is returned to wardrobes.

Use a breathable garment cover.s

Breathable fabric covers allow air to circulate while protecting clothing from dust. They prevent moisture and odour‑causing gases from becoming trapped around the garment. This is especially important for coats, suits, dresses, and occasion wear that are stored for long periods.

Avoid plastic long‑term

Plastic garment covers block airflow completely. Any residual moisture inside the fabric has nowhere to escape, creating a closed micro‑environment where bacteria and odour compounds can persist. Plastic should be used only for short-term transport — never for long‑term storage.

Rotate seasonal clothing

Clothes left untouched for months are more likely to develop odour because moisture and bacteria remain dormant inside the fabric. Periodic rotation—even briefly removing garments from storage—enables ventilation and reduces long‑term moisture buildup.

Maintain airflow in wardrobes.

Overcrowded wardrobes restrict airflow and trap moisture. Spacing garments, avoiding overfilling, and occasionally ventilating wardrobes prevent the formation of damp pockets where odour can redevelop.

Together, these habits keep fabrics dry, hygienically stable, and odour‑free over time. They not only prevent smells from returning but also extend fabric life by reducing moisture‑related fibre stress and bacterial damage.

When Home Solutions Are No Longer Enough

If any of the following patterns appear consistently:

-

Odour returns within hours — the garment smells acceptable straight after washing or drying, but once worn or stored briefly, the damp smell reappears rapidly.

-

Multiple washes fail — repeated washing, changing detergents, higher temperatures, or adding products (vinegar, bicarbonate, boosters) produce little to no improvement.

-

The smell worsens over time — instead of staying the same, the odour becomes stronger, appears faster, or spreads to surrounding garments in storage.

These are clear indicators that the problem has moved beyond what domestic laundry can resolve.

At this stage, bacteria and moisture are no longer present on the fabric’s surface. They are embedded deep within fibre cores, seams, linings, padding, and layered constructions. Each additional home wash introduces more water and heat without fully removing the bacterial fuel source, reinforcing the cycle rather than breaking it.

This is the point at which professional garment care is no longer a luxury or a cosmetic upgrade — it becomes corrective maintenance. The goal shifts from making clothes smell better temporarily to resetting the fabric hygienically at the fibre level, removing trapped moisture, bacteria, and residue so the garment can return to long‑term odour stability.

Continuing with home solutions beyond this point often accelerates fabric wear and frustration, while professional intervention addresses the root cause directly.

If damp smells keep returning after washing, the problem is not cleanliness — it’s trapped moisture inside the fibres.

Professional garment care removes odour at its source by controlling moisture, temperature, and fibre stress.

Message our Hampstead garment care team on WhatsApp to properly stop damp odours.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do clothes still smell damp after washing?

Because moisture and bacteria remain trapped deep within fabric fibres, especially in thicker garments and in humid indoor environments common in London homes.

Can professional garment care permanently remove damp odours?

Yes. Professional garment care addresses odour at the fibre level by removing trapped moisture, bacteria, and residue using controlled temperature, humidity, and drying processes.

Final Thoughts: Why Clothes Smell Damp Even When Clean

If your clothes smell damp even when clean, the problem isn’t cleanliness — it’s moisture control at the fibre level.

If your clothes smell damp even when clean, the problem isn’t cleanliness — it’s moisture control at the fibre level.

What most people experience as a “mystery smell” is actually a predictable outcome of how fabrics behave, how bacteria survive, and how London homes function. Washing removes visible dirt, but it does not automatically reset a garment’s internal environment. Moisture can remain hidden deep inside fibres, seams, linings, and padding long after clothes appear dry and fresh.

London’s climate plays a major role. High outdoor humidity, limited sunlight, indoor drying, closed windows, and compact living spaces all slow evaporation. As a result, clothes often move from wash to wear to storage without ever reaching true internal dryness. This creates ideal conditions for bacteria to survive in a dormant state, then reactivate when warmth and moisture return.

Fabric structure makes the issue even harder to solve at home. Cotton absorbs moisture into its core, wool traps it between fibres, and synthetics seal it between layers. These differences mean that a single wash-and-dry routine cannot work equally well for all garments — even though it may look successful on the surface.

This is why the odour keeps returning. The smell is not a failure of effort, frequency, or hygiene. It is the result of moisture and bacteria being left behind in areas that domestic systems cannot fully reach.

Once this distinction is understood, the solution becomes clearer. Preventing damp smells is less about washing more and more and more about drying correctly, controlling humidity, allowing fabrics to stabilise, and recognising when professional intervention is needed.

Understanding the difference between clean-looking and hygienically stable clothing is the real turning point. It’s the first step toward stopping the cycle — and finally solving the problem permanently.

Still struggling with laundry that never feels truly clean?

Repeated washing doesn’t fix deep moisture, bacteria, or fabric damage. Professional laundry care does.

👉 Book a professional laundry collection in Hampstead

👉 💬 WhatsApp us for a fast quote

No comment